Last Updated:November 06, 2025, 13:08 IST

Born from Bhutto’s post-1971 resolve and shaped by AQ Khan’s covert enrichment drive, Pakistan’s nuclear programme grew through decades of espionage, foreign help & global silence

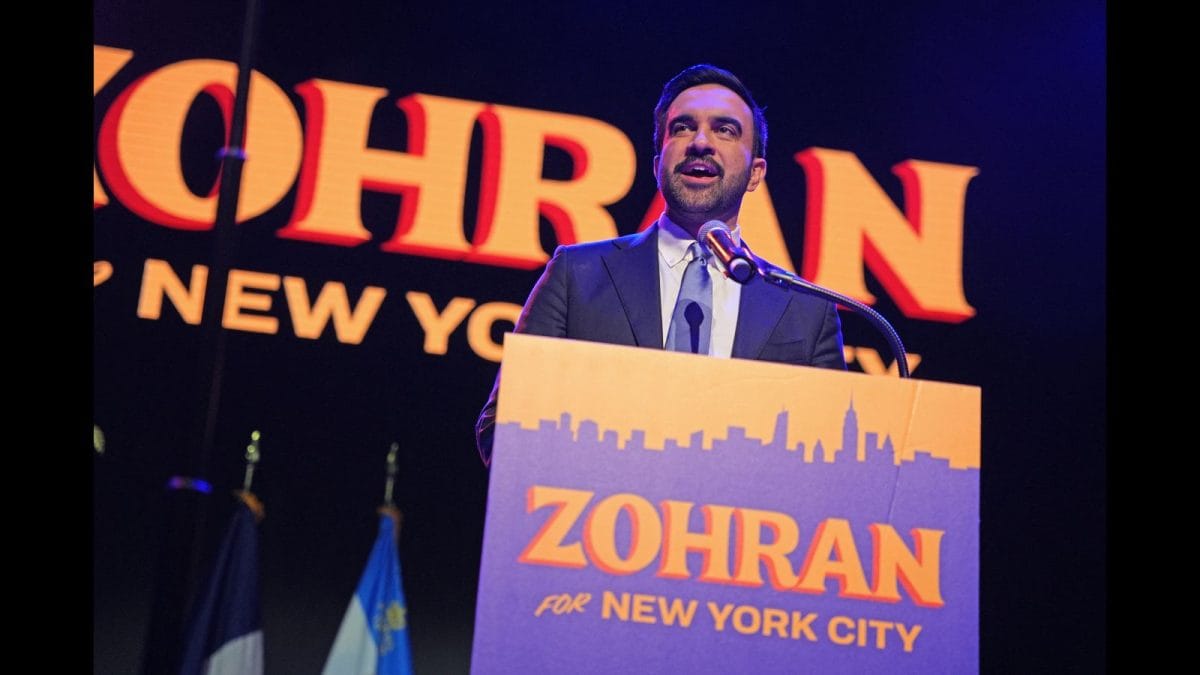

Pakistani youths with a model of a Pakistani Ghauri missile celebrate Pakistani nuclear tests during a night time rally on May 30, 1998. (Reuters)

A senior Pakistani official recently reiterated that Islamabad “will not be the first to resume nuclear tests", responding to US President Donald Trump’s claim that countries such as Russia, China, North Korea and Pakistan are secretly testing nuclear weapons underground, while the US remains the only major power refraining from doing so. Pakistan, the official reminded CBS News, “was not the first to carry out nuclear tests and will not be the first to resume them."

Trump’s remark briefly revived global attention on one of the most secretive nuclear programmes of the twentieth century, and the question of how Pakistan, a developing country under sanctions through much of the 1980s, managed to acquire the bomb at all.

The answer lies in a mix of espionage, foreign help, scientific ambition and geopolitical calculation that unfolded over three decades.

How Did Pakistan’s Nuclear Race Begin?

Pakistan’s nuclear ambition did not begin with India’s 1974 “Smiling Buddha" test, but that explosion made the pursuit inevitable.

The humiliation of the 1971 war, which led to the creation of Bangladesh, had left Pakistan militarily weakened and psychologically scarred. In the years that followed, then-Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was determined to rebuild the country’s self-image. He had already told a meeting of scientists in Multan in January 1972, just weeks after the war, that Pakistan must develop a nuclear option.

“If India builds the bomb, we will eat grass or leaves, even go hungry, but we will get one of our own. We have no other choice." Bhutto once said, a line that captured the mix of desperation and defiance driving Pakistan’s new policy.

The same year, Bhutto reorganised the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission (PAEC) under nuclear engineer Munir Ahmad Khan, who had previously worked at the Atomic Energy Agency in Vienna. The PAEC, created in 1956, had benefited from the US-sponsored Atoms for Peace programme, which gave Pakistan training and a small research reactor. Yet these early efforts were entirely civilian.

In 1974, Pakistan also signed a deal with France to purchase a plutonium reprocessing plant, but under pressure from Washington, Paris cancelled the agreement in 1976. That setback deepened Bhutto’s conviction that Pakistan could rely only on itself.

Bhutto convened top scientists, military officials and bureaucrats, tasking them to initiate a covert nuclear-weapons programme, codenamed ‘Project 706’.

Initially, Project 706 focused on plutonium production through reprocessing spent fuel from the Canadian-supplied Karachi Nuclear Power Plant (KANUPP). But this route soon hit obstacles. Canada and the US curtailed cooperation after 1974, and Pakistan lacked both a reprocessing facility and access to sufficient plutonium. The Nuclear Suppliers Group, formed in 1975 in response to India’s test, further tightened export controls.

It was at this point that a new player entered the scene. A young metallurgist named Abdul Qadeer Khan, then working in Europe, reached out to the Pakistani government offering his expertise.

His arrival changed the direction of the entire programme. Bhutto, sensing an opportunity to bypass the plutonium bottleneck, authorised a parallel uranium-enrichment track. Under Khan’s leadership, a new laboratory was set up at Kahuta, near Rawalpindi, which would soon become the nucleus of Pakistan’s nuclear effort.

AQ Khan And The Stolen Centrifuges

In the early 1970s, Khan was employed at URENCO, a European consortium based in the Netherlands that specialised in gas-centrifuge technology used to enrich uranium. Through his work, he gained access to sensitive design drawings and supplier lists. When he returned to Pakistan in 1975, he brought not only technical blueprints but also supplier lists, allowing Pakistan to replicate a complete enrichment system from scratch.

By 1976, the Kahuta facility, later renamed the Khan Research Laboratories (KRL), had begun assembling its first centrifuge cascades. Western intelligence agencies quickly suspected theft. In 1983, a Dutch court convicted Khan in absentia for nuclear espionage, though the ruling was overturned on a technicality.

Khan’s work paid off. By the mid-1980s, Pakistan was believed to have produced enough highly enriched uranium for at least one bomb, though it refrained from testing. Scientists at the PAEC and KRL conducted several “cold tests" of bomb designs without actual detonation.

Building The Bomb: Smuggling Networks And Foreign Help

Pakistan’s success was neither isolated nor entirely indigenous. It depended on a dense network of international suppliers, covert financing and foreign government support.

The European black market: During the 1970s and 1980s, Khan’s network sourced vacuum pumps, maraging steel, frequency converters and precision tools from firms across Europe. Some suppliers acted knowingly, others were misled by front companies. Investigations decades later uncovered a supply chain stretching from Switzerland and Germany to Malaysia and Dubai.

China’s critical role: Declassified American intelligence assessments point to direct Chinese assistance to Pakistan’s weapons effort. According to the Security Archive at George Washington University, by 1983, US officials believed Beijing had provided not only technical expertise but also a tested nuclear-weapon design, commonly referred to as the CHIC-4 model. China is also reported to have supplied 5,000 ring magnets in the mid-1990s to stabilise Kahuta’s centrifuges, as later confirmed by the US State Department.

Financial and diplomatic backing: Middle Eastern allies, particularly Saudi Arabia and Libya, extended financial aid to Pakistan through the 1980s, officially for conventional defence cooperation but indirectly easing budgetary pressures on the nuclear project. At the same time, Islamabad maintained plausible deniability, insisting its research was for peaceful purposes, while the military ensured secrecy around Kahuta and other sites.

By 1990, the bomb was essentially complete. Pakistan had mastered uranium enrichment, refined bomb design and developed delivery systems through collaboration with China and North Korea, including the Ghauri missile, derived from Pyongyang’s Nodong. What remained was the political decision to test.

The US Knew, But Looked Away

Washington’s relationship with Pakistan’s nuclear programme is one of studied ambivalence. The US knew what Islamabad was doing but repeatedly chose geopolitical necessity over non-proliferation principles.

Under the Symington and Glenn Amendments, US law barred aid to countries pursuing unsafeguarded enrichment. Yet after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, Pakistan became the front-line ally in America’s proxy war. Through the 1980s, the Reagan administration certified annually under the Pressler Amendment that Pakistan did not possess a nuclear explosive device, despite intelligence indicating otherwise.

The aid, worth billions, included F-16 fighter jets and economic packages. When the Soviet withdrawal was complete, then-President George HW Bush refused certification in 1990, triggering sanctions. By then, Pakistan had already crossed the threshold.

After the 1998 Chagai tests, President Bill Clinton imposed fresh sanctions, lifted only after 9/11 when Pakistan became a vital partner in the war on terror.

Several former officials have since acknowledged the deliberate ambiguity. Former Dutch prime minister Ruud Lubbers revealed in 2005 that the CIA had discouraged Dutch prosecutors from acting against Khan in 1975, preferring to monitor the network rather than dismantle it. Washington’s selective blindness effectively gave Pakistan time to perfect its arsenal.

From Chagai To The World’s Nuclear Club

On 28 May 1998, Pakistan conducted five underground nuclear explosions in the Chagai Hills of Balochistan, responding barely two weeks after India’s Pokhran-II tests. A second round followed on 30 May. Then Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif announced that Pakistan had “settled the score", and AQ Khan appeared on state television as the architect of the bomb.

The tests made Pakistan the world’s seventh declared nuclear power and the first Islamic nation to possess the bomb. The country also declared a unilateral moratorium on further testing and maintained that its weapons were purely defensive, but refused to sign the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), citing India’s position and national security needs.

The Proliferation Web Exposed

While Pakistan consolidated its nuclear status, A.Q. Khan’s enterprise quietly morphed into a transnational proliferation network. Between the late 1980s and early 2000s, it supplied centrifuge designs, components and know-how to Iran (P1 and P2 designs later renamed Ir-1 and Ir-2), Libya and North Korea.

The operation unravelled in 2003 when a German-owned ship, the BBC China, was intercepted en route to Libya carrying centrifuge parts traced back to Khan’s network. Libya’s subsequent decision to abandon its weapons programme exposed the scale of Pakistan’s export ring.

Under international pressure, President Pervez Musharraf placed Khan under house arrest in 2004 after a televised confession. Khan claimed he had acted independently; many analysts doubt that assertion, arguing that Pakistan’s military could not have been unaware. Musharraf pardoned him, and the matter was quietly closed within Pakistan, though Western agencies continued to dismantle remnants of the network for years.

Were There Attempts To Assassinate AQ Khan?

No confirmed attempt on Khan’s life has ever been documented, but the idea of neutralising him or his facilities was seriously considered by several intelligence agencies.

During the 1980s, India and Israel reportedly discussed a joint strike on the Kahuta complex, modelled on Israel’s 1981 attack on Iraq’s Osirak reactor. The plan was shelved after concerns that it could trigger a regional war.

According to Israeli investigative journalist Yossi Melman, writing in Haaretz, Mossad’s then chief Shabtai Shavit admitted that had the agency correctly interpreted Khan’s intentions in the 1980s, he “would have considered sending a Mossad team to kill Khan and thus change the course of history".

Mossad and Israeli military intelligence, Melman wrote, had tracked Khan’s extensive travels across the Middle East but failed to grasp that he was setting up a global proliferation network.

Melman’s account added that Khan, after helping Pakistan build its arsenal, became the “godfather of Iran’s nuclear programme", selling centrifuges which Iranian scientists, led by Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, later adapted.

Melman also described how Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi ultimately exposed Khan’s network in 2003 when he approached the CIA and MI6, fearing a US invasion after Iraq. Gaddafi shared documents showing how Khan’s associates were building nuclear facilities for him, some disguised as chicken farms.

Melman called Khan “one of the few nuclear scientists who helped Israel’s enemies acquire game-changing capabilities yet died in his bed of natural causes".

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Today

Today, Pakistan is estimated to possess around 170 nuclear warheads, according to the Stockholm Peace Research Institute’s (SIPRI) Yearbook 2025. SIPRI notes that Pakistan continues to develop new missile delivery systems and produce fissile material at a steady pace, signs of a country actively expanding its arsenal despite lacking transparency or robust oversight mechanisms.

Unlike India, which maintains a declared No First Use policy, Pakistan’s nuclear doctrine remains deliberately ambiguous and heavily focused on short-range tactical nuclear weapons, designed for battlefield use.

SIPRI suggests that Pakistan’s arsenal could grow further over the next decade, especially as it tries to match India’s advancing delivery systems and strategic capabilities.

The Story Comes Full Circle

Trump’s suggestion that Pakistan might be secretly testing again has no public evidence behind it, and Islamabad continues to insist on its testing moratorium. But his remark serves as a reminder that Pakistan’s nuclear programme was born and built in secrecy, and that opacity still defines it.

Karishma Jain, Chief Sub Editor at News18.com, writes and edits opinion pieces on a variety of subjects, including Indian politics and policy, culture and the arts, technology and social change. Follow her @kar...Read More

Karishma Jain, Chief Sub Editor at News18.com, writes and edits opinion pieces on a variety of subjects, including Indian politics and policy, culture and the arts, technology and social change. Follow her @kar...

Read More

First Published:

November 06, 2025, 13:07 IST

News explainers Pakistan Denies Trump’s Nuclear Test Claim, But How Did It Build The Bomb In The First Place?

Disclaimer: Comments reflect users’ views, not News18’s. Please keep discussions respectful and constructive. Abusive, defamatory, or illegal comments will be removed. News18 may disable any comment at its discretion. By posting, you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Read More

2 hours ago

2 hours ago